Devil in the Details: Rest, Relief, and Frame Semantics - Episode 121

In this episode of Genesis Marks the Spot, we finally dive into a long-anticipated topic: frame semantics—a cognitive linguistic tool that could revolutionize how we approach biblical texts. From exploring how the word "rest" is more than just a Sabbath nap, to rethinking the identity of the Satan in Job and why the Sons of God are unique, this episode is a thoughtful journey into how meaning is framed, shaped, and sometimes flattened when we don’t consider conceptual structures behind words.

The usual truth-conditional semantics (where meaning hinges on objective truth) contrasts with the more holistic and contextual approach of frame semantics which is a better fit for the approach of biblical theology. Whether you’re a seasoned theology nerd or new to these ideas, this episode will challenge how you read Scripture—and may just spark your next Bible study breakthrough.

Topics Covered:

What is frame semantics, and why does it matter for Bible study?

How our language frames the way we think (and vice versa)

The nuanced difference between “rest” and “relief”

Why “the Satan” in Job might not be who you think he is

Cognitive vs. structural approaches to Scripture

How to use this tool in your own studies (and a call to collaborate!)

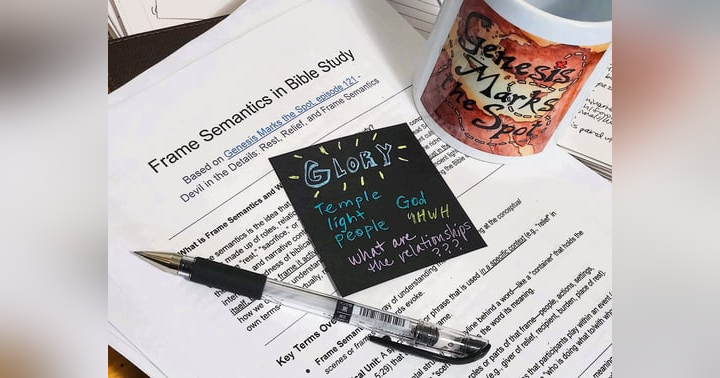

Don’t forget to download the handout mentioned in the episode for a visual aid to the concepts discussed. Want to help develop the next version? Carey is looking for collaborators!

Download link: https://genesismarksthespot.com/downloads/frame-semantics

Feedback or framework requests? Reach out at GenesisMarksTheSpot.com or connect on Facebook!

**My Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/GenesisMarkstheSpot

Music credit: "Marble Machine" by Wintergatan

Link to Wintergatan’s website: https://wintergatan.net/

Link to the original Marble Machine video by Wintergatan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvUU8joBb1Q&ab_channel=Wintergatan

In this episode of Genesis Marks the Spot, we finally dive into a long-anticipated topic: frame semantics—a cognitive linguistic tool that could revolutionize how we approach biblical texts. From exploring how the word "rest" is more than just a Sabbath nap, to rethinking the identity of the Satan in Job and why the Sons of God are unique, this episode is a thoughtful journey into how meaning is framed, shaped, and sometimes flattened when we don’t consider conceptual structures behind words.

The usual truth-conditional semantics (where meaning hinges on objective truth) contrasts with the more holistic and contextual approach of frame semantics which is a better fit for the approach of biblical theology. Whether you’re a seasoned theology nerd or new to these ideas, this episode will challenge how you read Scripture—and may just spark your next Bible study breakthrough.

Topics Covered:

- What is frame semantics, and why does it matter for Bible study?

- How our language frames the way we think (and vice versa)

- The nuanced difference between “rest” and “relief”

- Why “the Satan” in Job might not be who you think he is

- Cognitive vs. structural approaches to Scripture

- How to use this tool in your own studies (and a call to collaborate!)

Don’t forget to download the handout mentioned in the episode for a visual aid to the concepts discussed. Want to help develop the next version? Carey is looking for collaborators!

Download link: https://genesismarksthespot.com/downloads/frame-semantics

Feedback or framework requests? Reach out at GenesisMarksTheSpot.com or connect on Facebook!

**My Patreon: https://www.patreon.com/GenesisMarkstheSpot

Music credit: "Marble Machine" by Wintergatan

Link to Wintergatan’s website: https://wintergatan.net/

Link to the original Marble Machine video by Wintergatan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=IvUU8joBb1Q&ab_channel=Wintergatan

Welcome to Genesis Marks, the spot where we raid the ivory tower of the biblical theology without ransacking our faith. My name is Carey Griffel, and today we're gonna be riffing off of what we've just been talking about lately and we're gonna be getting into words. And honestly, I am super excited about this episode. I am finally going to talk about a thing called Frame Semantics. If you like Biblical theology nerdiness, this episode is going to be for you. Let me tell you what, I am so excited to talk about Frame Semantics. It's been on my docket to talk about for a long time, and this week I have just decided this is a really good time to get into it.

As part of that conversation, I want to keep talking about [00:01:00] names like I did last week, and also things that aren't names, but they act like names. I wanna talk about Adam and Cain and Noah and the connections between them. But honestly, we might not. Okay. Probably won't get into that specifically today because in addressing frame semantics, I don't want to start with an unfamiliar example. I wanna start with something we've talked about and thought about a lot.

Now, if you are new to the podcast or to biblical theology or to divine counsel stuff, then maybe you haven't already thought a lot about these things that I'm gonna be talking about today, and that is absolutely okay. These will still be good examples to look at first. I really think this is going to be cool eventually when we have gone through some things and we've talked about it more, and we kind of solidify the idea in front of [00:02:00] us.

And actually I'm probably going to ask you guys for some help in developing some material, specifically Bible study material. But I will leave that for kind of the end of the episode today. So stick around for that.

And really, I genuinely think this is huge. I think we will be developing entirely new ways for you to study the Bible. And I don't think I'm kidding in that. And I'm not being hyperbolic, I'm not being a sensationalist. This is the kind of stuff that an academic scholar may or may not do. But I have never seen it translated down for the layman, and really, I've hardly ever seen it specifically brought out in biblical studies, but I've especially not seen it come out of the academy and I've not seen things in the way that I'm thinking of presenting it to you and [00:03:00] for you. And this isn't me making stuff up, it's me trying to translate it from that academy atmosphere to you to make it a useful tool.

Now that being said, if you have looked in the show notes, I hope that I will have a link there that will get you to a handout because a handout I think is going to be really useful for this episode. I hope that it will be done by the time this episode drops. I think at least the first iteration of my handout will be ready and I do plan on revising it and improving it, which is where your help can come in. But I have some other ideas for that as well. So again, stick around and I will talk a little bit more about that at the end. Probably.

Now you don't have to have the handout in order to listen to this episode, but it might be helpful because we're gonna be getting into some [00:04:00] details and I don't expect anyone to really grasp or fully understand the details that we'll be talking about today. But a handout will be really helpful if you see it actually laid out on paper in front of you. At least it will be helpful to a lot of us.

Alright, so instead of talking about names today, I'm gonna be talking about the Sons of God and the Satan in Job and we will be revisiting the theme of rest, since that's kind of what's kicked off my whole desire to finally get into frame semantics with you.

So let's look in depth on how words in general are used. They're used in the Bible in particular as hyperlinks, for instance, where a word or a phrase will call back to something else. Or a word can be used for a future author to reference and hyperlink back. There is even more than that because [00:05:00] words are not just a representation of a single thing.

Words can provide nuance. For example, we have rest and relief, very similar, but also with a different twist. Words can also load in more than their weight when they're used sometimes, and it's hard to know when that happens in the Bible, for instance, because it's an ancient text. Now when a word is loading in more than their weight, that is like a hyperlink. But it isn't just a callback to some passage in particular, but it can serve to aid a definition. Or it can load in qualities or attributes. One example is Sons of God that we'll talk about.

Of course, a potential issue here is that meaning can get lost through time and language can fall apart, and when it's put back together, it not [00:06:00] only loses nuance, but it can acquire meaning that it didn't have originally. A word that I think about for that is the word sacrifice. It had a particular meaning back in the Old Testament and the New Testament, and for us, the meaning of a sacrifice is different. That doesn't mean it's entirely disconnected, however.

But language in the Bible, then, becomes a bit of a minefield. How do we go about treating the original context fairly while still acknowledging that sometimes our ideas are different? Is it always bad to use a word in a new way? I don't think so, but when you're treating an ancient text as a formative text for us, we should probably understand it in that original context.

So we're gonna be developing concepts within a larger framework, and that is what we're going to use [00:07:00] frame semantics for. Now let's go back to this idea of rest versus relief. Again, like we talked about last week, Noah's name means rest. But Lamech said that Noah would grant relief. Now, this concept carries with it not just the idea of rest, which it might, but it also carries with it the idea of a change. So it's not just a rest for a moment, but a real change is what is hoped for. If you change that word to mean rest, as the Septuagint actually did, it doesn't necessarily change the meaning, but again, it loses some of that nuance that we might notice, though obviously, not everyone notices the nuance. Maybe the Septuagint translators wouldn't have changed it in the way that they did if they had, [00:08:00] so, nuance can be hard to see. Go figure.

But the good thing is concepts are usually easier to see, but they're also far more complex than you might think at first. We can use the metaphor of the frame, which is what we have in frame semantics. So we're gonna think of the concept as a frame or a container, or perhaps a plot of ground with a fence around it. Maybe picture a pen or a paddock with a bunch of sheep in it.

The concept, the paddock or the frame, is broad. It's easy to see, but you don't or can't always distinguish the differences between the elements inside the concept. And indeed, you might not notice the difference if you aren't looking closely. A lot of sheep look very similar, don't they? So the idea of rest and relief might look so [00:09:00] similar that you don't notice the distinction.

Now, that's only a beginning image, and here you're looking at the broad concept. We aren't always looking at the broad concept. We don't always see the frame, nor do we always see what goes inside of the frame. But these are things that we often instinctually understand as we grasp language on a really fundamental level.

So let's set aside the concept of rest again for a moment to look at a few other things. If you're confused after listening to this episode about what frame semantics is and all of the things that go on with it, I don't blame you. So take some time with this if you want to get into the particulars, because I will be bringing it up some more.

And a disclaimer as well. I feel like what I'm going to bring out to you is almost a whole thesis paper or even a [00:10:00] dissertation topic, and I am not an expert. And part of that is because it's just not used enough, or it's not described enough and brought out explicitly enough. Even in biblical scholarship. So admittedly, I'm going to go into some uncharted waters here, at least somewhat. Perhaps an expert in frame semantics or cognitive linguistics will take issue with what I'm going to say and how I'm gonna say it. But here we go anyway.

Frame semantics is a theory from cognitive linguistics. So think about how our brain and our language works in relation to the way we actually think. And that is a two directional thing. The way we think produces our language, but our language also affects the way we think. It's a two-way street there. [00:11:00] Frame semantics was primarily developed by Charles Fillmore in the seventies and eighties. It's based on the idea that words don't exist in isolation. They evoke entire conceptual structures or frames.

These frames are like mental scenes or situations that help us interpret the meaning of a word. Every single word activates a background structure of knowledge. This is what Fillmore called a semantic frame.

One of his examples is the word buy, like to buy something. The word buy evokes a commercial transaction frame, and that frame includes the buyer, the seller, the goods, and the money, or the thing that is paying for what you're buying. So to fully understand the word [00:12:00] buy, you implicitly understand the whole scene. You understand who's doing what to whom and why.

Now that might seem a little boring and obvious. Well, of course, all of these things are related. But again, you have the concept and you have the different elements inside of that concept. Words like sell, pay, charge, also evoke the same commercial frame, but from different perspectives. Like you're talking about the seller versus the buyer, for instance.

This is quite related to the work of Lakoff and Johnson with the subject of metaphors. If you're a fan of the Bible project or if you've taken Dr. Heiser's AWKNG classes, then Lakoff and Johnson might ring a bell. Metaphors do something a little bit similar to this, where you have a source, the metaphor's, imagery, and [00:13:00] you have a target, the thing that it's actually referencing. There's a relationship there that is generally broader than one single item or quality. So you can describe more with less, and you end up with more in your head with just that metaphor than you would with a simple description.

But frame semantics isn't a metaphor and it's a deeper idea, but just like how we have a metaphor and you have images and ideas being brought together that can actually shape the way we think, a conceptual frame can do that as well. And this happens automatically on levels we don't really perceive consciously.

Lakoff, Johnson, Fillmore, and many others have done a lot of work to show that our knowledge and understanding of the shape of reality really doesn't rest in single words or ideas [00:14:00] in isolation. Really, we first go to figurative and conceptual image before we go to a specific meaning. If someone says a word to you, you do not actually think of it concretely first.

I'm going to give you a list of key concepts in frame semantics. Don't worry about trying to understand them now, but I want you to be familiar with them.

You have the frame which I have already described as that conceptual framework.

You have lexical units. A lexical unit is a word that is going to evoke a frame. So you have the word and then you have the frame.

We have something called semantic roles, and we're really not gonna get much into those today. But a semantic role is the position within the frame that [00:15:00] corresponds to different participants or agents involved in an event or a situation. So it's kind of like what they're doing and how they're relating to one another.

But the three main things that we're gonna be dealing with today are the frames, the lexical units, and the frame elements. Now, a frame element is one of the participants or props that are involved in the frame.

So let's go back to the word buy. The word buy is the lexical unit. The frame is the commercial transaction. The frame elements are all of the key components of this framework. You have the participants, the buyer, and the seller. You have the objects, the goods, and the money. You have the actions, like the transaction itself. You might have a setting [00:16:00] or a condition. You can have a purpose or a goal. There will be a result or an outcome. One person loses money and gains an item, the other person loses the item and gains the money.

Okay? So all of that is a lot. I know. And I don't expect you to remember any of that other than the fact that we have the lexical unit or the word and the frame, and then the elements inside the frame, and all of those elements are being brought up when we use that word.

I'm really sad that this is not talked about specifically in biblical studies. It's a cognitive linguistic thing, but we are dealing with an ancient text that we need to decode and understand it. So this is really helpful stuff. If you happen to be familiar with schema theory, it's very similar to that. And of course, people [00:17:00] in biblical studies do use this. I see it all the time. It's just not explicitly called out for what it is. The Bible project uses it all the time.

The fun thing about frame semantics is that there are frames within frames like a system of cells, inter interlinked within cells, inter interlinked within cells, interlinked with a stem.

Okay? So we're going to play with this idea. Feel free to go check out that handout that you can actually use yourself if you can kind of grasp what we're doing here. Now, it might be a little bit hard at first when you don't quite understand all of the elements, but that's why we're here. We're gonna learn about it.

Why is frame semantics useful and different from other ideas? Well, there's several key ways that frame semantics is going to help us. It's gonna help us a lot in studying the Bible because it [00:18:00] is dependent on context based meaning. It emphasizes the meaning of words and phrases as derived from the context in which they appear rather than isolated definitions. Traditional theories often analyze words or sentences all by themselves without a context. Frame semantics considers the broader conceptual framework that provides that context. So biblical theology is an absolute shoo-in for this kind of stuff.

Frame semantics is also all about holistic knowledge. It says that understanding a word requires access to all kinds of essential knowledge related to that word, which explains why we struggle with many areas of the Bible and understanding it.

Frame semantics is also about mental structures, and it helps us organize and [00:19:00] interpret knowledge and experience. It provides ways to see the elements and relationships between those elements that aren't described well in traditional semantic theories. You can see how if your thinking is based on mental structures that we've constructed ourselves, then moving cross-culturally or through time requires us to shift our frames to understand the other people either in the other culture or in the past.

Frame semantics also allows for recognition of interrelationships between words within the same frame, so that actually doubles and triples our knowledge of something to increase exponentially as we understand more and more. This is a very cognitive approach. It is part of cognitive linguistics, which argues that knowledge [00:20:00] of language is not really unlike other types of knowledge. Other theories say that knowledge of language is entirely separate from other types of knowledge.

Now, here's the kicker. Frames semantics rejects truth conditional semantics. Okay, so what is truth conditional semantics?

Truth conditional semantics, and that's whole mouthful, is something that you can think of as very literal or plain readings of something. So think about the literal six day creation, and I'm not trying to rag on that idea. But it's a really good example of what truth conditional semantics does and looks like.

So in truth conditional semantics, the meaning is held in truth conditions. For instance, the sentence, snow [00:21:00] is white, means that snow is white because it is true when snow is white. Like it doesn't allow any other interpretation other than mapping the word snow onto snow and white onto the color white.

Now, when we go into the idea of six day creation, somebody who thinks in truth conditions will say that God wouldn't have said that he created in six days if he did not, in fact, create in six exact literal days. In this framework of truth conditions, if God didn't create in six days, then the description of him creating in six days would have no meaning, or it would be a lie, one or the other. It wouldn't be true. It wouldn't have any meaning in and of itself.

So in truth conditional semantics, the meaning of a complex sentence is [00:22:00] derived systematically from the parts of the actual sentence. It doesn't really matter where the context of the sentence is in because the meaning is behind the words of the sentence. Every bit of the sentence is a reference to something that is true or factual, or else you're lying.

And frankly, truth conditional semantics has a hard time with metaphor, if you ask me. Some metaphors, not all, can be literally false, but metaphorically true. Now, the ways that truth conditional semantics will deal with that is they will talk about something like analogical truth or they'll adjust the range of true and only apply the truth claim in part. Like God is a rock. Well, God isn't literally a rock, but God is literally sturdy or strong or firm. So [00:23:00] it will take part of the referent and use that as its truth claim.

Now, there's several problems with truth conditional semantics. It basically ignores context. It has a hard time with abstract idealization. Truth conditional semantics also simplifies or ignores pragmatic factors like the speaker's intent to maintain its truthfulness. In other words, it ignores the specifics of the speaker and the intent and the context.

Okay, so now let's compare frame semantics and truth conditional semantics. I hope you can see that a lot of us have grown up in the world of truth conditional semantics. In both of these views, truth is located in a different place. For the truth conditional, a statement's [00:24:00] meaning is equivalent to its truth conditions, so you have to have an objective state of affairs to be necessary to be true. Like the objective state of creation in six day creation is that God actually used 6 24 hour periods and that he created light first, and all of these things that are absolutely exact and how it happened. If something in the statement is not true, then this statement is not true.

Truth conditional semantics, conflates, or mixes together, the idea of meaning and truth. The meaning is the truth or the objective fact, at least in theory. And I say in theory because even though a literal creationist will insist upon the objective situation at play, they will still move on to the [00:25:00] meaning of God and creation that is really not dependent on those facts. And there's really no cogent way that they do that from one to the other. The meaning of God and creation is something distinct from the fact of creation.

And I see that in say, a commentary like Fruchtenbaum's Ariel Bible Commentary, where he goes to great lengths to explain that creation was literal and has to have been literal, but then he expounds on the meaning of creation and none of the meanings that he brings out have anything at all to do with science or a literal six day creation, or the order of creation or any of that. There's a distinctive movement from fact to meaning, and there's a really no connection there.

Now, I don't want to put down truth conditionals entirely [00:26:00] because it is very good for formal logic. In fact, formal logic requires it. And you know what? I really like logic. So let's not entirely get away from that. But at the same time, we can't logic our way through scripture. It just doesn't work.

So now let's talk about frame semantics. In frame semantics, truth emerges from coherence with activated frames, which is a structured network of various elements of knowledge. So meaning, and thus truth, depends on that contextual understanding within the framework.

Truth in frame semantics relies on shared cultural or experiential knowledge. For example, the word sell requires familiarity with commercial transactions. And in the [00:27:00] Bible, understanding six days requires that contextual frame of the temple. Here, words are not just there as words, but they have a role to play within the frame.

Frame semantics handles metaphors and idioms beautifully, and it explains how a statement can be true within the frame, even if it is literally false, such as poetic or figurative language.

Frame semantics is perfect for a Hebraic mindset where knowledge is equal to experience. Of course, this is not strictly a frame semantics reality. Not everyone using frame semantics is going to have a Hebraic mindset, but frame semantics helps us see a different way of viewing the world and organizing it [00:28:00] because it can work within contextual meanings and mappings.

Frame semantics is a far better tool to see what the Bible is saying compared to truth conditional semantics. Remember, it's not about facts being a thing, like the correspondence between the word and an object. It's that meaning is not encapsulated or limited by those correspondences between word and object. Truth and meaning is found in words, but also in frames.

Now, a Hebraic conceptualization of the world is in particular frames that understands knowledge as experiential, right? Like Adam knew his wife, Eve, and that's a euphemism because experience is how you get [00:29:00] knowledge of something.

Now, truth conditional semantics and frame semantics can be somewhat complimentary in ways, but they are incompatible for a worldview foundation. In essence, truth conditional semantics anchors truth in external reality. But frame semantics anchors it in internal cognitive structures. And so those two things are complementary. But again, you can't use both at the foundation of your thinking.

And it's not that one negates the other, but the values of a culture can set in motion the way that we think. Think of our modern Western world and its values of logic and objectivity and exactitude . Then think of a Hebraic mindset where knowledge is experiential and communal and it's gained through action, through [00:30:00] participation, through real experience, and that is not the same as taking out your measuring tape and measuring a table's length.

We struggle to explain the Hebraic mindset within our framework today, but in fact, even though we value and utilize truth correspondence all over the place, it really is the fact that we do not leave meaning fully in that domain. I don't think you can do it. I think we have to make those leaps to meaning that go beyond facts. Just like the meaning behind creation doesn't consist merely of the facts of creation.

So let's bring all of that into the meaning of the Sabbath. For someone who is truth conditionally oriented and they're using that as a tool, it is really important that the six days of creation map on to [00:31:00] literal days, because then the six days of our work week will also map onto those six literal days, one-to-one correspondence of objective time. And really the tool and the hermeneutic are basically one and the same.

Now for someone who is using frame semantics as a tool, the tool is not the same as the hermeneutic, but someone using the tool can see and organize information for a culture that is oriented to understand truth as experience. You really can't do that in the other framework. So here, the truth of creation and the Sabbath is, well, maybe I'm gonna say this wrong or not exactly right, but the truth of creation and the Sabbath is within the experience of it. The meaning is that it is something that you're gonna do and experience in a real [00:32:00] way.

The meaning doesn't reside in whether or not God actually created in the explicit way that he laid out in Genesis one. God's actions in creation have a place in the overall frame, but they don't encompass or embody or limit the meaning. Just like the meaning in God stretching out the heavens as a tent in, I think it's Psalm 1 0 4, that meaning there is not in the fact of God stretching the sky out like a tent, but the meaning resides in the conceptual framework of the tent.

Oh, hang on, there's a tent. What is a tent? A tent has to do with the tabernacle, the exodus, the wilderness wanderings, and probably a whole lot more stuff is in that conceptual frame that we aren't tracking with if we don't see it as a frame.

So you see how the tool of frame semantics fits [00:33:00] perfectly within trying to understand biblical truth in a very biblical theology way, meaning all the stuff that I talk about and that Dr. Heiser talked about and that the Bible project talks about. You don't get themes and design patterns without something like frame semantics.

Someone who is absolutely married to truth conditions simply cannot do the same thing. Their understanding of knowledge and truth does not map onto that. In fact, I might go so far as to say that it's adamantly opposed to it, which isn't always a problem because as I said, my suspicion is as much as we like truth correspondence, we do not always really do it all the time. Even if we think that we do.

I am not saying that there aren't truth correspondences all over scripture. [00:34:00] But the fact of Moses's existence has less to do with the meaning of the Exodus than his actions do. And so also, any details of his life that aren't recorded or that don't have to do with the biblical story, they are completely and utterly irrelevant and don't matter to what's going on. And of course, I'm not just talking about Moses here.

And so frankly, that is a big claim to make because if the biblical story doesn't, for instance, tell us who Abram was worshiping before we see him called out, well, that information isn't relevant to the meaning. It might be interesting and it might be really annoying to us, truth conditionalists, who want to know things. We want details. And so we will turn to speculation of fact.

I hope you guys can [00:35:00] see how important this is to wrap our minds around. It might seem pedantic and granular at some level, but I genuinely think it's a game changer. And the cool news is many of you are already doing this, you just didn't know it. I personally think it's helpful to know the nitty gritty details because then you can recognize it when it shows up and when you're doing it.

And again, I'm not saying you need to give up on truth conditions or that experiential knowledge always trumps or is better than truth conditional based knowledge. As I said, we really probably all naturally emphasize experiential knowledge in many ways. Having this information in hand will give you something to consider.

For instance, which way am I thinking about something in particular? Whatever it is that you're studying, what is the difference in meaning if you look at it from truth conditions [00:36:00] or if you looked at it in a conceptual framework?

Another question, how do specific truth conditionals that we're looking at when we study connect to contextual, experiential knowledge? Or do they?

How can the things I learned from the context and ancient mindset be moved into my current truth conditional way of thinking? Because that's a fair question. That might be part of the application process of things. When we're doing Bible study. We have a long tradition, especially in the church of flattening the text and the meaning.

Okay, so we've been talking about truth conditionals and frame semantics. Now I'm going to compare and contrast a structuralist approach to language, which is like that truth conditional semantics versus a cognitive approach.

A [00:37:00] structuralist approach or an approach that is creating systems, right? Systematic theology. It looks at grammar. It looks at form, pattern, abstracts. The language system is not always the same as the instance of an actual use of a word, right? Because it is more concerned with the whole picture. It wants to create the pattern and the form.

Now the cognitive approach looks at how the brain actually processes things. It is very focused on meaning and language as connected to thinking, and it's based on actual use. It is not disconnected from the actual use of language.

So again, you can think of a systematic approach to biblical interpretation and doctrine versus a biblical theology approach. A systematic approach doesn't take [00:38:00] into account the individual authors, but rather it asks a question like, what does the Bible say? As if the Bible is an entity that speaks for itself. And really come to think about it, I think many people use that question or that phrase as if the Bible is what God says, right? What does the Bible say? It's the same as, what does God say? And frankly, I think that's a bad way to see things. Because the Bible is still made up of texts, written by humans in particular and different contexts.

Like, yes, you have the ultimate author, God, the proximate authors, the humans, but God doesn't overwrite the humans in a way that only his meaning is coming across as a whole, but not in the parts somehow. We somehow want the Bible to [00:39:00] say something as a whole that goes beyond the individual books and authors, and I'm just like, I don't think that's how we should be looking at that.

What the Bible says doesn't have to correspond to some imaginary, complete view of what God would say. Now, a biblical theology approach says, what does this author say? Because that human author is rooted in time and context with a particular set of things they were thinking and trying to communicate. And behind the meaning of what that individual human author says is what God says too. Even if that's not what the entire witness of scripture says as a whole if you patterned out all of the individual instances into an abstract pattern.

The cognitive biblical theology approach should inform the structural or systematic approach. It's not like we have to toss that out, [00:40:00] but let's face it, it often doesn't do that. We frequently look at only, or mainly, or firstly, the abstract patterns, and we are not looking at the instances of the intended meaning or the original message in context. It's almost like we don't care about those instances because we only care about what the Bible says.

As an example, let's look at Satan or the Devil as an abstract or a formula or a single being that contains the whole pattern. And it's interesting that we do that because he transcends time in a way that other beings don't. Like he's not transcending time in the same way that God does because God isn't held within finite time, but the devil exists from beginning to ending, [00:41:00] the whole entire Bible, right? We have him there more or less anyway, and interestingly enough, we don't see any other being described like that, even the gods of the nations, and that's probably what makes Satan the arch enemy. He's kind of evil in a structural way.

Now, let's look at the Satan in Job, in a particular instance here. Systematically, we erase the distinctions in this story when we jump immediately to the abstract patterns.

The distinctions in the story in Job is that the Satan is a being that functions within the Divine Council. Now whether or not you see him as a paid employee of the Divine Council is irrelevant to that because the Divine Council is clearly a frame element in the story. God is holding a council and the Satan is present as a [00:42:00] participant of that council.

A structuralist or a systematic view has really no explanation for why the Satan doesn't show up again as an important element after the first two chapters. God's interaction with the Satan suggests a relationship that is far more complex than a structuralist view of Satan as the arch enemy of God. Because why would God use or work with his arch enemy? That doesn't make sense within the story. And while something doesn't have to make sense for it to be there, let's look at the range of meaning here.

The semantic range of the Satan as the devil in a structuralist view is that he is God's main opposer, but the semantic range of the Satan in a cognitive approach is that that the Satan is adversarial, which is more [00:43:00] nuanced than being God's main opposer. A cognitive approach might investigate the particular function that the Satan holds in the story. An adversary is not necessarily, again, a main opposer or even an enemy because an enemy implies mutual opposition.

The Satan is a frame element. He is the prosecuting attorney of the counsel, and again, it doesn't matter whether or not he's rebellious here. Although a suggestion: what if God does in fact use rebellious beings for his purposes? Just like we see in the exile, both going into and going out of. Satan is not portrayed as an outright enemy because again, enemy suggests that God is working against versus working [00:44:00] with, like he would be doing a prosecuting attorney for a purpose. Really, the Satan functions as less a character in the story that matters. He's more like a test, really, like the Tree of Knowledge is not a character, the Satan really isn't a fully fledged character either. The Satan functions in a certain way. He moves Job from possibly having a transactional relationship with God to Job solidly understanding that it's about devotion, not transaction.

. We can see how the cognitive or frame semantic approach is really helpful to seeing a Hebraic experiential understanding of knowledge. Because here the Satan's role is understood through the embodied experience of testing opposition, legal proceedings, justice, judgment, and concrete [00:45:00] realities. It goes beyond a simplistic, good versus evil dichotomy.

A truth correspondence or a systematic view would likely insist that his inclusion means that the story is transmitting a timeless truth about a single being. The Satan must be the devil because well, eventually, separate instances were structured or systematized into this one being.

A frame semantics view is not about that systemized view because it's engaged in understanding the instance, the example, the particular thing we have in front of us, and understanding that within the conceptual, cognitive framework of the story, the original context of the original writers and readers, and focused on the meaning behind all of that.

The eventual pattern into propositional fact [00:46:00] of a broader character of the devil, well, that's something that fits within a frame of the New Testament, but it doesn't fit inside a frame from the Old Testament. So you see, frame semantics allows the Old Testament to have its frames and the New Testament to have its frames, and they're related, but they're not the same.

A systematic approach is blind to the instances and contexts because it's not asking for that meaning behind that particular lexical unit, within that particular text. It's asking for a structural or a patterned meaning behind all of the things that are added together.

Now you can't do biblical frame semantics in English, I'm sorry to say, but that doesn't mean you're doomed if you don't know the original language, because there are many tools to see behind the language. You can use one [00:47:00] of the more literal translations that tries to use the same word throughout scripture, translating it the same way.

You can use an interlinear. You can still do word studies. Yay, they still have their place. Like we learned that the word in Genesis 5 29 is not actually the broader word for rest, but a narrower word for relief and comfort. And because of frame semantics, we don't need to divorce that word from the concept of rest, just because it's not the same word. With frame semantics, we can see how it fits into the broader frame and gives nuance to a particular instance.

Okay, so I know this is kind of getting long and I know I'm doing a little bit of repeating myself here, but it's hard to do an introduction if I don't actually do the introduction and give you some examples. So again, we have, broadly: the frame is the concept, and then we have the [00:48:00] frame elements that are the things in the frame. And we have the lexical unit that brings it all up to our brains.

So back to the fact we can't do frame semantics in English. The Satan in Job is a really good example because it has that distinct lexical unit of the Satan. The Satan, and Satan, the devil, like the proper name Satan, are not entirely the same. Again, the truth correspondence side will say that they are the same because they map them the same. They see the pattern and they say, well, that makes it the same. It doesn't really matter here that the Satan is not a name. Because obviously, hey, it's the same dude.

But from a contextual perspective, looking specifically at the Book of Job, that actually doesn't have to be the case. And further the [00:49:00] meaning of Satan as arch nemesis of God doesn't seem to be showing up here. Because again, no matter what the Satan's orientation towards God is, God isn't in an adversarial position himself. As I've said, there are conceptual links between the serpent and Genesis and the Satan and Job and the devil in the New Testament.

Those conceptual links are what allowed the New Testament authors to pattern it all together and come up with one concept of Satan as the devil. The fact that the New Testament authors put those pattern pieces together into a truth correspondence of devil and arch nemesis does not mean that the author of the Book of Job was doing that or thinking that in any way. He seems to only have been making a conceptual connection, [00:50:00] not a propositional or ontological one. And yeah, I think that matters. It matters to the meaning of the story. Conceptual frames are not the same as a truth correspondence where you have this thing is that thing.

Now we can stop here for a second and ask, why on earth would the New Testament cognitive frames be different than the Old Testament ones, even though they're still retaining a lot of that hebraic mindset? Well, it's because of the development of Greek logic, which had a massive impact in the second Temple period. I believe this is also why you see Second Temple Judaism literature with all its speculations. Like 1 Enoch, the Book of Jubilee's, they are making truth correspondences.

And maybe I shouldn't get into a second [00:51:00] example, but I really want to, to kind of help you see this. We're gonna talk about the sons of God, and this is another example of why you can't do frame semantics in English.

The lexical unit that we have here is Bene Ha Elohim, which is what we have in the Book of Job. And the Bene Elohim are also what show up in Genesis six, right? And I think it's Job 38.

So let's actually break this down in a frame semantic way. The lexical unit Sons of God evokes the divine council frame. It activates that ancient near Eastern cultural framework of a heavenly court where divine beings assemble before God. And in Job, these sons of God are members of God's celestial court. They're not humans. And in Job 38, 7, they shout for joy at creation. In Genesis [00:52:00] six, they come down from heaven. But the concept of being son of God is evoking that whole concept of God as king and having children that are part of his court.

So we have frame elements like the divine sovereign. We have God presiding over the council. We have the council, a bunch of celestial beings subordinate to God. In Job, we have an adversarial role, the Satan, as a participant also in this council.

Now, there is a broader framework of general sonship. We might call this adoptive sonship because of the way it's used in scripture. In adoptive sonship, we have humans. We have Israel as God's son in Exodus 4 22. Even in the New Testament, we have believers as children of God in Romans eight 14 through 17. We [00:53:00] have kings and leaders, the Davidic Kings anointed as God's son in Psalm two, seven. This is also a christological concept, Jesus as the unique son of God.

In this framework, sonship implies covenantal belonging, representative authority, and it's not the same as the sons of God in the Old Testament. There are two separate things. In the Divine Council framework, we have spiritual beings, the royal court, cosmic government and justice. In the adoptive sons frame, we have covenantal relationship that is that framework. The participants are humans, Jesus, the whole nation of Israel, and the context is redemptive history, we might say. The function for the adoptive sonship framework is identity, inheritance, [00:54:00] and redemption, right? So if you look at those two frames, they are different. They're not the same even though they might be using words that sound alike.

Why does it matter? Well, we can see how the same lexical root can map to different frames depending on context and we risk misinterpretation if we don't take the framework into account. And if we don't take that cultural context, if we don't understand it, we are lost at understanding any of this.

A systematic or other type of approach can conflate terms or replace them. And to them it doesn't matter because they have a patterned it all out and called it all the same. They've flattened the whole thing. It doesn't matter if it says Sons of the Living God. It doesn't matter if it says God's son, or Bene Elohim. It's [00:55:00] all the same to them. But you can see when you look at the frameworks that these are within, they're not the same.

Alright, so let's go ahead and wrap this back up into rest and I would call it maybe a divine rest framework. Frame semantics is all about relationships between roles and elements and things like that. Now, I think we can see, and I've talked about last week, that the big frame here isn't just about taking a break, but really a broader, better conceptual frame is something like cosmic order, divine presence, covenant eschatological and redemptive hope.

Okay. So we have that framework of, we might call divine or cosmic rest. Now let's look at some lexical units that would activate the frame, because there are many of them. We [00:56:00] have the word rest, we have the word relief, we have the word sabbath. We have the word dwelling or tabernacle or temple. The concept of inheritance also plays into this, which is pretty darn cool. That's not something you're gonna think of when you normally think of rest as just stopping work, right?

But if you think about it, inheritance has a lot to do with it because of the rest that the people are getting when they enter the land. They are gaining their inheritance and rest at the same time because the land is a place of rest. And as I pointed out last time, we also have a connection with Shalom, which is ultimate order, and that kind of a peace that we can have with God. Jesus in Matthew 1128 says, come to me. I will give you rest.

So all of those things can activate the [00:57:00] frame of divine rest. Those are lexical units that activate it, right? So when the word is mentioned, the framework pops up, and all of these things are kind of there in the background.

Now let's look at the roles that are played in this framework. We have the Divine Agent, God or Yahweh, or Jesus. We have the recipients. We have the people at the time of the flood, or Noah, at least in his family, Israel, humanity as a whole, or Christians in particular in the New Testament. Exiles. The land itself gains rest. So the land functions as an element. Then we have burden and toil. This is an element that is part of the framework. Labor, slavery, exile, sin, and death all connect in this way.

As we've said [00:58:00] many times already we have relief and rest, and both of those are nuanced, but similar. They're parallel. Physical, rest, spiritual renewal, covenant fulfillment. Time factors into this as well. The seventh day of creation, the Sabbath cycle, the jubilee years , and the eschatological day of the Lord. Place also, factors in. We have the garden, we have the promised land, we have the temple, we have new creation and the new heavens and the new earth.

We have ritual and symbols and signs like festival times, which were connected to the tabernacle and temple and God's presence. And then there's goals and functions for this as well. Rest is to bring up the idea of restoration, healing, worship, the presence of God, [00:59:00] cosmic order finally being restored and everything being in shalom and righteousness. I mean, look how cool this is, that all of these things are brought in just when we mention a word like rest.

Now, I want to mention also the conceptual framework might have the same word as the lexical unit or even one of the frame elements, but that doesn't mean the concept as a whole, that like whole frame doesn't map onto only one instance or only one lexical unit. I mean, that's why we have the two things. The lexical unit is bringing up the frame, and they might have the same word. You might call them the same thing, but the conceptual framework is always going to be broader than the lexical unit.

So now let's get into that ancient mindset and think about [01:00:00] cultural and theological contexts that feed into this frame. In Genesis one to two already we have creation climaxing in God's rest and temple enthronement. We have the story of the flood, which I also argue is a form of literal actual rest and relief.

Many other places in Genesis, but we also have Exodus from slavery to rest in the land. And what's really cool here is that, you know, you have that word relief in Genesis 5 29 in regards to Noah and the flood, right? Well, you can think of the exodus and the eventual entering into the land as a kind of relief and then a rest. I just love seeing those connections from Genesis one to 11 throughout the rest of scripture.

In Leviticus 25, we have the Sabbath year, we have the Jubilee, and that is [01:01:00] a rest for land and the people. In Joshua, we have God who gave them rest on every side, the conquest to covenant fulfillment. Isaiah 40 to 66, there is a major theme of comfort for exiles, and this is all about divine relief and rest. Of course, we have Jesus's ministry. He was actively healing on the Sabbath. How is that not part of giving relief and rest? Right? Hebrews three and four, we mentioned that one last time. Eschatological rest as a final destination and a culmination in all of this. Then of course, to the end of Revelation where we have temple restoration in a cosmic way. Super cool stuff right?

As I said, we have frames within frames and cells, interlocking within cells, interlocking with cells. Our overlapping frames are things like the temple, exodus, [01:02:00] deliverance creation, covenant, eschatological hope. The divine rest frame tells the story of God's ruling, bringing creation from disorder and chaos and deconstruction even, and reconstruction and loss and chaos again. Slavery, toil, bringing all of that into a state of order, presence, peace, shalom. It's a pattern that is reflected in time and space and identity as to who we are. We end up with the culmination of the image of God throughout all of this process as well.

This helps us understand why Sabbath isn't just about not working, why rest is a kingdom of promise. Why relief is tied to righteousness and shalom, which is both sides of the concept of justice, right? We might have some punishment [01:03:00] going on, but we have recovery and healing and wholeness. We have the temple and garden intimately linked, and we have resurrection as a restoration and not just an escape from this world.

Some of my favorite things to actively talk about. I really hope you guys have found this episode helpful and I hope that you are at least a little bit excited about frame semantics. I think this can really help notch up our Bible studies if we're doing this in a way that actually approaches things to help give us those frameworks to think about things in a more holistic way and to understand this interconnectedness that scripture gives us.

Now, like I said, I really hope that I do have that handout in the show notes today, but I also know that that handout is only going to be a rough draft of what I ultimately want to do. So if [01:04:00] I could have your help, if I could have you test out that handout with actual practice. You can fill out the frames we've already talked about today. Or you can go and find a new lexical unit and a new conceptual framework. Try to fill that out and see what that gets you. If anybody wants to do that, and then come show me what you end up with, I would love to see that. Absolutely would love it.

But also I would like to call out anybody who wants to help me to develop something that's better than that, and I really genuinely mean that. I need some help to do this. I need feedback on what you wanna see, on how clear it is, on if it's really helpful, on if you enjoy doing it, if there's anything we can add to it, anything we can improve. I would absolutely love for you guys to contact me and say, I would love to help you with this project. It doesn't have [01:05:00] to require a lot. If you wanna help me out, I probably will have some ideas on how we can actually get together and work together on this project. If you're interested in that, you can contact me on Facebook. You can contact me through my website at Genesis Marks the Spot.com.

And also I think that I'm going to develop a chat GPT that is going to go along with these handouts that I'm developing. And the reason I'm doing that is for a couple of reasons. Number one, I've just been using it a lot lately and I've noticed how useful it is for some applications. So what I'm envisioning here is that along with the handout, which is kind of blank because you can put any word in and concept that you're looking at, but you don't wanna do that and then not really be able to get anywhere with it. You know, if you get [01:06:00] like a mental block, you don't know how to fill it out, or you don't quite understand it yet, or you're trying to develop it and use it for other people, and you don't wanna do it in a way where you don't really understand the best way to fill it out or whatever, right?

So I'm thinking if you use the chat GPT in relation to your work, in the handout, then it either can be helping you with practice or it can help you check what you've already developed and see if there's some additional ideas or things that you missed, or it can help you to actively create a worksheet for other people that you can actually do yourselves. And you can do that without a whole lot of work for yourself, because I know everybody's busy and if you're trying to develop a Bible study or do something with people, that can be time prohibitive. Plus, you don't wanna just sit there flailing and being like, I don't know if I did this right, or [01:07:00] whatever. And the chat GPT should be able to help guide you in that process and kind of give you that little boost and those helping hands kind of a thing. Right? That's my thinking.

That's what I'm planning. If you're interested, come let me know. I would love to have your help. Really excited about this episode and I hope you enjoyed it. Thanks for listening and thanks for sticking with me here to the end of the episode and entertaining my little idiosyncrasies and trying to find better ways to do Bible study.

I appreciate all of you. If you have questions and if there's particular things that you want me to go through like in an episode or something like that, like there's a particular framework or lexical unit that you want me to actually lay out in this process in an episode, I would be more than happy to do that. I want to give more [01:08:00] examples and so we'll be doing that already. So if you have one in mind that you would like me to tackle, I'd love to hear it.

At any rate, I will go ahead and wrap up and say thank you to all of you who are financially supporting me. Really deeply appreciate all of you guys. You can find out how to do that on my website at genesis marks the spot.com, where you can also find artwork and blog posts and guest profiles and other fun things. Do let me know if you have further questions or anything you would like to hear me kind of work out and tackle. I appreciate you all and I wish you all a blessed week and we will see you later.